Hemingway’s Unbelievable Survival in the African Wilderness

How two plane crashes in forty-eight hours nearly ended a literary legend—and forged one of the greatest true stories of his life.

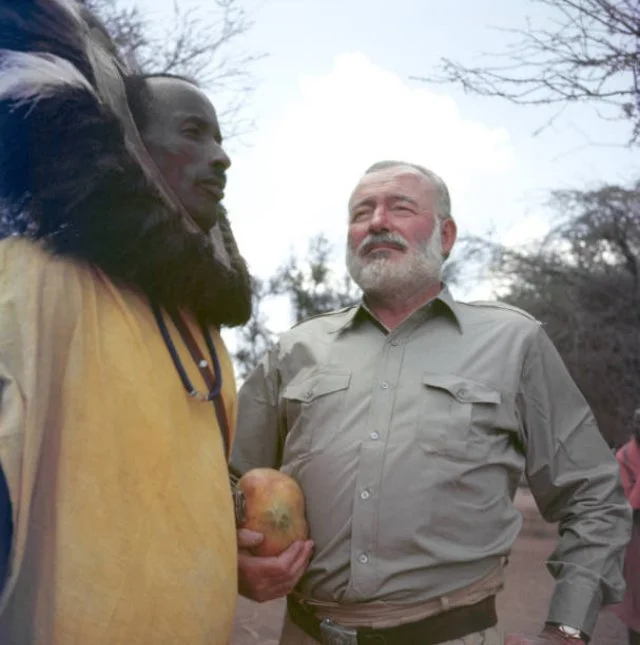

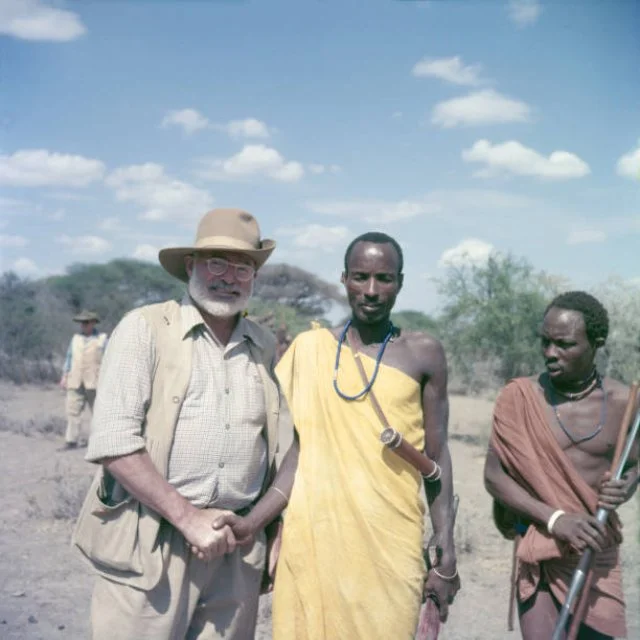

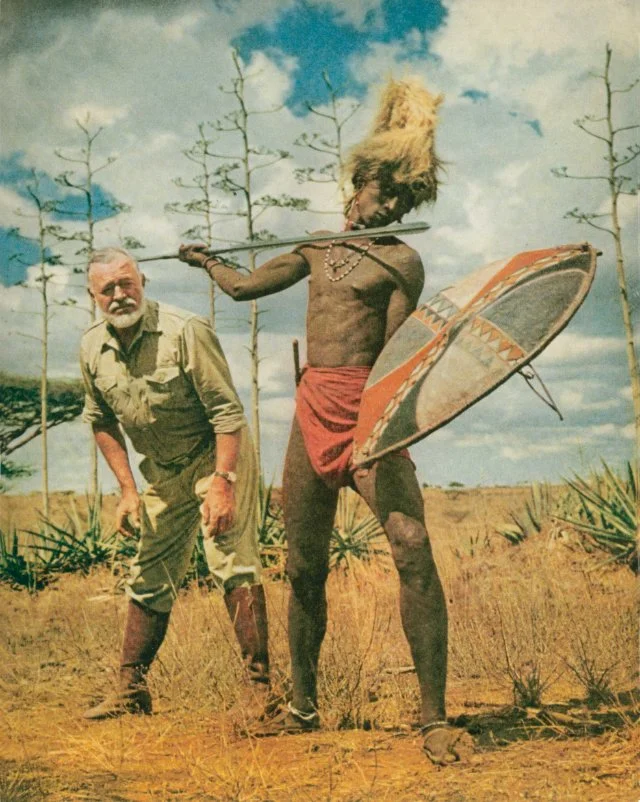

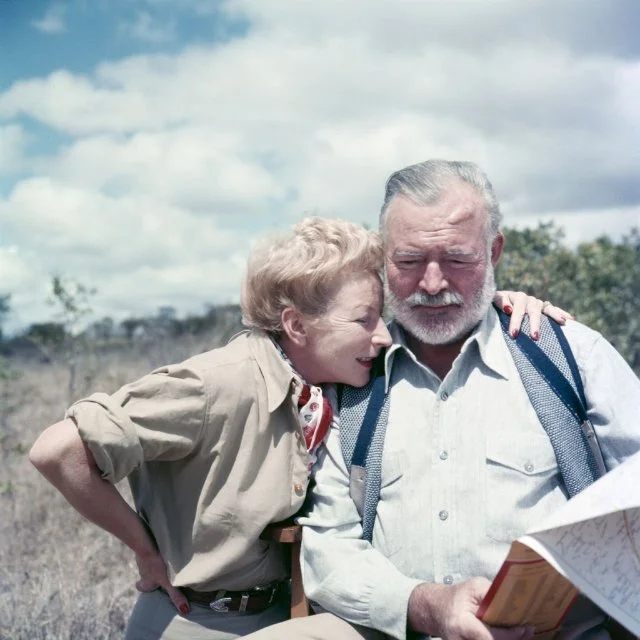

Few episodes in literary history feel as cinematic or as perilous as the moment Ernest Hemingway cheated death not once but twice in the African wilderness. We commemorate one of the most harrowing and legendary chapters in his life: the back to back plane crashes he survived during his 1954 trip to East Africa. What began as a celebratory journey for Hemingway and his wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, transformed into a saga that tested every ounce of his resilience. On January 21, 1954, while flying in a small Cessna piloted by the seasoned bush pilot Roy Marsh, the couple soared low over Murchison Falls in Uganda. Marsh dipped the plane along the winding Nile to give them a closer look at a herd of elephants. In a split second miscalculation, the aircraft clipped a telegraph wire and spiraled into the thick brush along the Nile River, turning a sightseeing flight into a violent crash.

Miraculously, all three aboard survived, though not without injury. Hemingway emerged limping, his shoulder badly bruised and ribs cracked; Mary suffered vertebral injuries and deep contusions. The jungle around them was eerily silent except for the pinging of the cooling engine. As darkness settled over the African bush, the Hemingways found themselves stranded beside the wreckage, waiting out a night that felt longer than time itself. By early morning, a rescue party located them and transported them to the remote village of Butiaba on the shores of Lake Albert. Meanwhile, newspapers abroad, relying on scattered early reports, mistakenly declared Hemingway dead, a grim foreshadowing of just how precarious the next forty eight hours would become.

On January 23, 1954, a de Havilland rescue plane arrived to fly the Hemingways from Butiaba to Entebbe for medical care. But their escape was short-lived. Moments after takeoff, an electrical fire erupted inside the cabin, filling the tight space with choking smoke. The pilot aimed for an emergency landing in the towering papyrus reeds along the fringes of Lake Victoria, but the aircraft slammed into the wetlands with crushing force. For the second time in two days, Hemingway was thrown into a mangled aircraft, surrounded by splintered metal, fire, and confusion.

The second crash was far more punishing. Hemingway, dazed and concussed, discovered that the cabin door had jammed shut. In a feat that has since become part of his legend, he rammed his shoulder and then his head against the door until it finally gave way, allowing Mary and the pilot to escape. Exhausted and battered, they trudged through reeds and mud until they reached Entebbe. When they finally arrived, clothes torn, faces blackened with soot, Hemingway holding a battered cigar, onlookers stared in disbelief. In less than two days, he had survived two plane crashes and walked out of both wrecks under his own power.

The injuries he sustained during those back to back crashes would follow him for the rest of his life, yet his survival became one of the defining myths that surrounded him. The story endures because it captures Hemingway at his most human and his most indomitable: bruised, burned, concussed, but unbroken. These days in East Africa reveal not just the dangers he faced, but the fierce willpower that shaped both the legend and the man, a reminder that even in the heart of chaos, Hemingway refused to let fate write the final line.