Bearing Witness in Spain

Why Ernest Hemingway Went to War as a Reporter and Why His Presence Mattered

Ernest Hemingway’s reporting from the Spanish Civil War occupies a singular place in twentieth century journalism and literature because he did not observe the conflict from a safe distance. When Ernest Hemingway went to Spain in 1937, he believed that bearing witness in person was not optional, but essential. For Hemingway, war could only be understood at close range, where ideology collapsed into lived experience.

Hemingway traveled to Spain as a correspondent for the North American Newspaper Alliance, but his motivations extended beyond professional obligation. The war, which pitted the Republican government against the Nationalist forces of Francisco Franco, represented to him the clearest early confrontation between democracy and fascism in Europe. He viewed Spain as a warning of a wider catastrophe and believed that an American writer of his stature had a responsibility to be present while the outcome still appeared undecided.

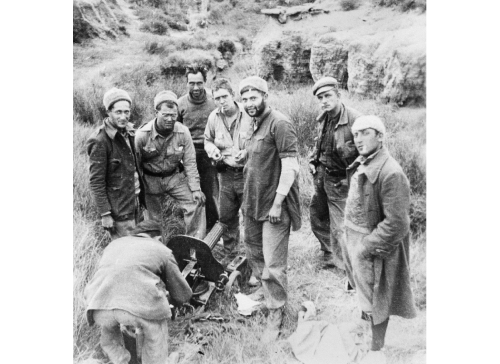

Hemingway arrived in Spain in late February 1937 and based himself primarily in Madrid, then under near constant shelling and aerial bombardment. He remained in the country for several months, reporting through the spring of 1937 as the capital endured siege conditions and Republican forces struggled to halt Nationalist advances. During this period, he traveled repeatedly to front line positions, including areas affected by the Battle of Jarama, speaking directly with soldiers and civilians rather than relying on official briefings.

The importance of Hemingway being in Spain lay not only in what he reported, but in who he was. By 1937, he was already one of the most widely read American writers in the world. His physical presence at the front lent visibility and urgency to a conflict many Americans regarded as distant. His dispatches emphasized fear, exhaustion, and endurance rather than heroics, helping reframe the war as a human tragedy rather than a political abstraction.

Hemingway’s involvement did not end with that initial stay. He returned to Spain again in 1938, extending his engagement with the conflict over more than a year. During this time, he also collaborated on the documentary The Spanish Earth, using his public profile to raise awareness and support for the Republican cause in the United States.

What ultimately emerged from Hemingway’s extended time in Spain was a profound shift in his work. His reporting grew darker and more reflective, and his experiences became the emotional and narrative foundation of For Whom the Bell Tolls, published in 1940. Hemingway left Spain convinced that the war had been lost as much through international indifference as through military defeat. His months on the ground ensured that the conflict’s human cost was witnessed, recorded, and preserved in both journalism and literature.