Hemingway on the Silver Screen: Celebrating 93 Years of A Farewell to Arms

On December 8, 1932, audiences filled theaters across America for the premiere of A Farewell to Arms, Paramount Pictures’ ambitious adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s celebrated 1929 novel. Directed by Oscar® winner Frank Borzage, the film was a prestige production from the start, blending literary sophistication with the star power and artistry of early sound era Hollywood. Ninety-three years later, it stands as one of the defining works of its period, a film that brought Hemingway’s modern prose to life through sweeping visuals and timeless emotion.

Anticipation and Star Power

When the project was announced, anticipation was immense. Hemingway’s novel had become a literary sensation, admired for its realism and emotional intensity. Paramount’s purchase of the screen rights for $80,000, roughly $1.5 million today, reflected the studio’s faith in both the material and its author’s growing cultural stature. In the midst of the Great Depression, such an investment demonstrated how deeply Hollywood believed in the story’s cinematic potential.

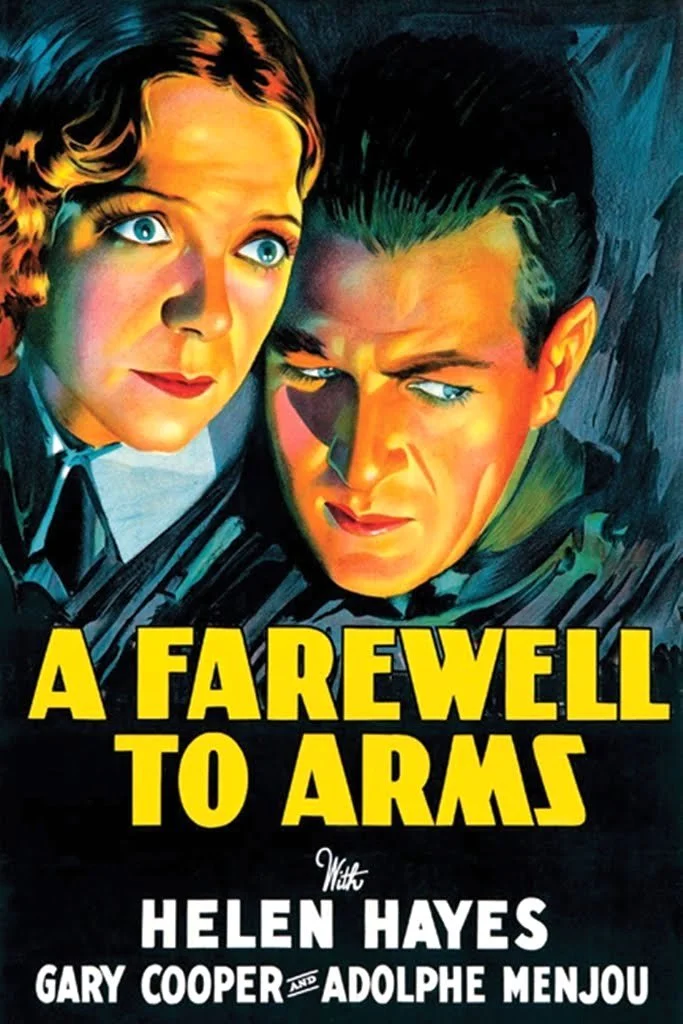

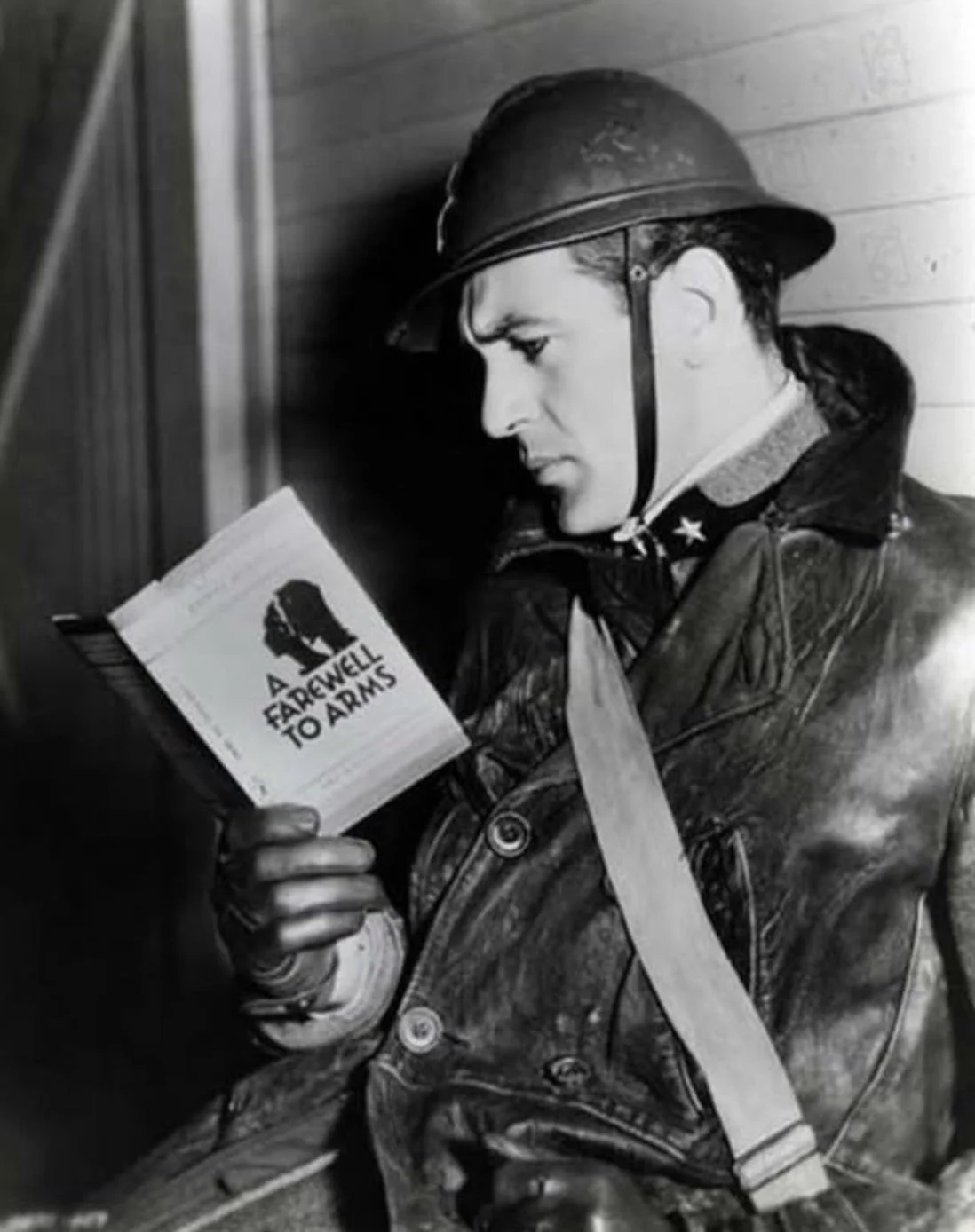

The cast only heightened the excitement. Gary Cooper, already emerging as one of Hollywood’s most magnetic leading men after Morocco and The Virginian, was perfectly cast as Lieutenant Frederic Henry, embodying the quiet strength and integrity associated with Hemingway’s heroes. Helen Hayes, widely regarded as the First Lady of the American Theatre, brought grace and emotional warmth to Catherine Barkley, while Adolphe Menjou lent sophistication and wit to the role of Captain Rinaldi. Together, the trio gave the story both depth and humanity, creating performances that continue to resonate with audiences today.

Behind the Scenes

Director Frank Borzage approached the film with his signature romanticism, infusing the tragic love story with visual poetry and an emotional sweep that made it one of the most beautiful productions of its time. He used light, shadow, and atmosphere to mirror the tenderness and tragedy at the heart of Hemingway’s story. The Alpine settings, the candlelit interiors, and the haunting rain-soaked finale all became hallmarks of Borzage’s lyrical style.

In an interesting production detail, the studio filmed more than one ending, allowing exhibitors to choose the version they felt best suited their audience. The first was the Hemingway ending, faithful to the novel, in which Catherine dies in Frederic’s arms, and the second was the “Hollywood Ending” where she lives. The studio and distributors opted for the Hollywood ending at first, but later distributed the film internationally with the Hemingway ending. In some cases at select American theaters, moviegoers could choose which ending they wanted to see. While this was unusual for the era, it reflected Paramount’s belief in the story’s universal appeal and the flexibility of early Hollywood storytelling. The result was a film that balanced artistic sensitivity with commercial vision, earning the admiration of both critics and audiences.

Reception and Legacy

A Farewell to Arms was met with strong acclaim for its performances, direction, and technical innovation. It received four Oscar® nominations and won two, for Best Cinematography and Best Sound Recording, affirming its place among the finest films of Hollywood’s Golden Age. It was also listed among the National Board of Review’s top ten films of the year.

The story’s power was such that Hollywood revisited it twenty-five years later with a lavish 1957 remake starring Rock Hudson and Jennifer Jones, directed by Charles Vidor. Though grander in scale and filmed in color, the original 1932 version remains the more emotionally intimate and artistically enduring of the two.

Ninety-three years after its debut, Borzage’s A Farewell to Arms endures as a landmark of classic cinema. It captured the human side of war and love with rare tenderness, brought together some of Hollywood’s greatest talents at the height of their powers, and helped cement Hemingway’s reputation as a voice that could move seamlessly between literature and film.

Tap the link below to read more from Gary Cooper’s daughter Maria on the making of this classic.